This is part 2 of a 5-part series on the history of cannabis in the U.S.

The late 19th century was a time of profound change in human history. Sweeping advancements in manufacturing, transportation, and communication revolutionized the way we lived.

This period was also a time of great change for cannabis in all of its forms. From being a necessary staple of industrialized life, hemp would later be demonized and shunned in the fledgling United States. Likewise, products made as over-the-counter medicines that contained cannabis would face new regulations, and the recreational use of hashish in social circles would become not just taboo but illegal.

Let’s look at this dark period in cannabis history and examine what led to the sea of change in social perception and public policy.

The Industrial Revolution

The period between the 18th and 19th centuries saw the beginning of the industrial revolution. New methods of production were invented, giving rise to entirely new industries and new social classes. Transportation also evolved from the horse and buggy to the newly invented steam and internal combustion engines.

At sea, the maritime industry experienced a similar technological leap. The Age of Sail gradually gave way to the Age of Steam. The power of steam propelled new ironclad ships and no longer depended on the wind. As the wooden sailing ship fell the way of the horse, so did the demand for cordage and canvas, two of the major uses for hemp.

At the same time, cotton began to replace hemp as a fiber crop, thanks to advances in textile manufacturing.1 The arrival of the cotton gin made cotton cheaper to harvest and process, making large-scale production possible.

In fact, hemp production in the US reached its peak in the mid-1800s,2 followed by a gradual decline, coinciding with the arrival of steam and cotton gin. In one fell swoop, three of hemp’s foremost applications (canvas sails, cordage, and textiles) were supplanted by new alternatives.

The US Census of 1850 counted 8,327 hemp plantations (defined as farms with a minimum of 2,000 acres).3 The industrial hemp they produced was used for cloth, canvas, and cordage for baling cotton. By the next century, only a handful remained, caused by new alternative products for hemp, as well as the negative perception of cannabis to come.

The War That Killed Cannabis

Advances in maritime propulsion and textile manufacturing gradually killed industrial hemp. However, a different factor altogether caused public perception to turn against the versatile plant. The roots began not in the US but hundreds of miles south.

In 1876, an ambitious Mexican general named Porfirio Díaz seized power in Mexico, a position he would hold on and off for 31 years. After seven terms as President, the Mexican populace finally had enough and rose up against Diaz in 1910, leading to the Mexican Revolution. It would last for ten years and become a defining moment in modern Mexican history. It would also cause a mass migration of Mexican refugees to the United States.

During the 1910s, there were 20,000 legal migrants from Mexico annually; by the 1920s, the number soared to between 50,000 and 100,000 per year as the war dragged on. Between 1900 and 1930, roughly 700,000 authorized Mexican immigrants entered the US, with nearly 90% settling in rural regions of the Southwest.4

The influx of immigrants escaping the Mexican Revolution brought with them new customs, including a more common use of recreational cannabis. As thousands of refugees streamed into the southwestern US, Americans only vaguely acquainted with either industrial hemp or medicinal cannabis were introduced to a new name: marihuana. The term also came with an emerging stigmatic reputation.

“Marihuana” Crosses the Border

Before the Mexican Revolution, hemp’s value in the US was primarily industrial, as the Indian hemp used had too little THC to have intoxicating properties. In the 19th century, Americans who wished to get buzzed mostly resorted to alcohol and opium. The use of Hashish, which was a compressed, highly potent cannabis flower, was already happening in some areas. Turkish hashish smoking parlors did exist along the eastern seaboard in the latter 1800s, including many in New York City,5 and attracted people from many social circles. However, alcohol and opium use was more common.

For Mexicans, however, opium was a luxury. Instead, they turned to the cannabis plant. They called it many names, including Rosa Maria, the "herb that makes one speak, and the "opium of the poor". Cannabis was enjoyed by both peasants, the upper class, and even both sides of the armed conflict. The popular folk song “La Cucaracha” references this common pastime:

La cucaracha, la cucaracha

Ya no puede caminar

Porque no tiene, porque no tiene

Marijuana que fumar

(The cockroach, the cockroach

Is unable to walk

Because he doesn’t have, because he doesn’t have

Any marijuana to smoke)

Initially a battle hymn by Mexican revolutionaries, the song became a cultural phenomenon across the country, even reaching its northern neighbor. It is “La Cucaracha,” in fact, that gave rise to the slang “roach” for the end of a joint.

Since most of the immigrants who fled to the US were poor and dispossessed, a social stigma began to develop around the newcomers. The brown-skinned immigrants streaming from the south were seen as alien and dangerous. This extended to their social customs, including the recreational use of cannabis, which was seen as “immoral” by many hostile Americans against immigration. As the flow of refugees increased, so did the resentment by the local populace.6

The Curtain Falls on Cannabis

The vast majority of the Mexican refugees settled in the Southwest, working as agricultural hands or unskilled laborers. As such, the first anti-immigrant legislation began in Southwestern states, primarily targeting cannabis.

In 1914, the city of El Paso, Texas, became the first US municipality to ban cannabis. The ordinance was sparked by an incident a year earlier when local police claimed that an immigrant high on cannabis stabbed a random pedestrian and chased another couple on the street.7

In an article in the El Paso Times dated June 4, 1915, the paper proudly proclaimed that "El Paso is the first city in the country to take a stand against the traffic in marihuana, known to be the deadliest drug on the market.” It also claimed that "Marihuana is known to create a lust for human blood in the users, and some of the most atrocious crimes committed in the city and elsewhere have been attributed to these fiends."

Later on, El Paso city officials, together with local representatives from the Customs and Agriculture Departments, would push the Secretary of Agriculture to ban the “killer weed” at the federal level. Their efforts were successful – after an official request from the Department of Agriculture, the Secretary of the Treasury would prohibit the importation of cannabis for non-medical use in 1915 under the Food and Drug Act.

On the state level, the first US state to outlaw cannabis was, of all places, California.8 In 1913, the Golden State amended the 1907 Poison Act to include "extracts, tinctures, or other narcotic preparations of hemp, or loco-weed, their preparations and compounds." Two years later, another amendment banned the sale or possession of "flowering tops and leaves, extracts, tinctures and other narcotic preparations of hemp or loco weed (Cannabis sativa), Indian hemp" except with a prescription.

Surprisingly, the amended law received little public notice since it was enacted as an obscure technical amendment by the California Board of Pharmacy. During this period, the first police raid against cannabis in the country also took place in California.9 In 1914, police in the Sonoratown neighborhood of Los Angeles raided two “dream gardens.” During this time, not many people in the state were familiar with the word “marijuana,” hence the paper had to explain what the drug was.

After California, a wave of anti-cannabis laws was passed in other states. Maine, Wyoming, and Indiana followed suit in the same year and Utah and Vermont passed similar legislation the year after. By 1933, 29 US states had criminalized cannabis,10 with the most serious penalties being in Texas, which allowed up to life sentences for mere possession.11

Finally, in 1937, the federal government passed the Marihuana Tax Act, which effectively outlawed cannabis at the federal level.12

A War of Words

During this time, there was a notable linguistic shift in cannabis that accompanied the changes in policy.

From early colonial history until the mid-1800s, cannabis was simply known as “hemp” and was strictly seen as an industrial product.

By the late 19th century, however, new medical applications for the plants were discovered, which began to be called by its Latin name “cannabis” (literally meaning “sourced from hemp”). Pharmaceutical brands of the time, like Bristol-Myers Squib, Eli Lilly, and Parke-Davis (now Pfizer), widely sold cannabis-derived medications – all labeled with the word “cannabis” – to treat a whole host of ailments ranging from migraine and insomnia to rheumatism.13 Up until the early 1900s, many scientific journals carried articles and studies on the medicinal and therapeutic effects of cannabis.

During the Mexican Revolution and the influx of southern immigrants, “marihuana” entered the American lexicon. In this context, it referred to the recreational or psychedelic properties of cannabis.

This is why the first anti-cannabis laws used the term “marihuana,” since they served to target both the recreational aspect, as well as the immigrant minority that used it. The terms used in the language of such laws make it even more clear, labeling cannabis as “loco weed.”

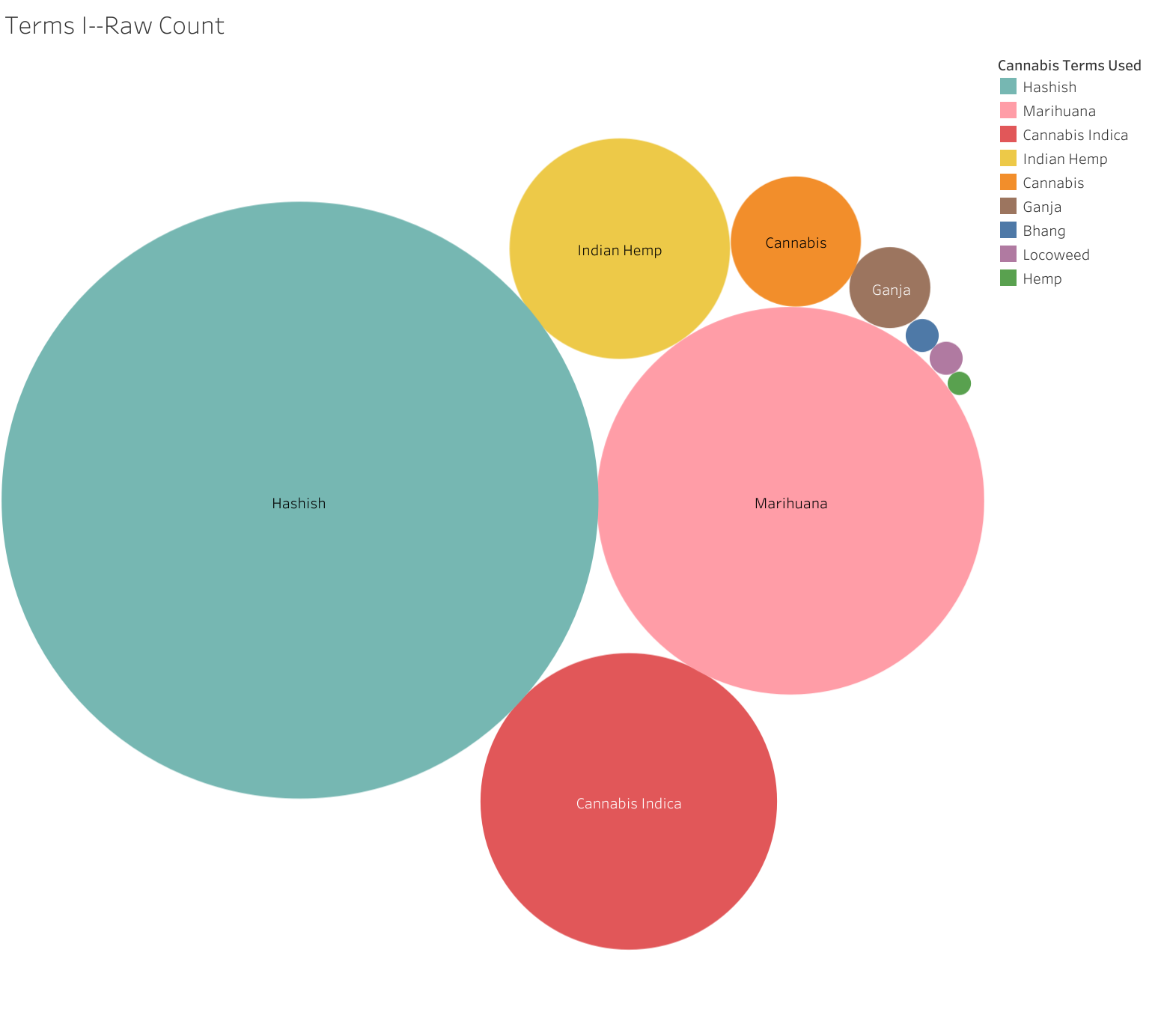

But surprisingly, most mass media of the day used another term for cannabis entirely: “hashish.” A study of American newspapers published between 1910 to 1919 by a University of Cincinnati professor found that most used the word “hashish,” followed by “marihuana.” “Cannabis indica” and “cannabis” came in third and fifth place, with “Indian hemp” being the fourth. The other terms used were “ganja,” “bhang,” and “locoweed.” “Hemp” came in last.14

What do the majority of these words have in common? They sound foreign and alien to American ears, a fact that was exploited by anti-cannabis crusaders of the day.

A good example of this is Harry Anslinger, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. In a series of public appearances across the US, he would consistently refer to cannabis as “marihuana” to drive home its foreign origin. During his Congressional testimony, he declared that “Marihuana is the most violence-causing drug in the history of mankind… Most marijuana smokers are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers.”15 This effectively sums up how public policy turned against cannabis in the US by combining it with anti-immigrant sentiment.

Similarly, when the Montana Legislature considered banning cannabis, it was equated with Mexicans. According to a passage in the January 27, 1929 edition of The Montana Standard:

“'There was fun in the House Health Committee during the week when the marihuana bill came up for consideration. Marihuana is Mexican opium, a plant used by Mexicans and cultivated for sale by Indians. 'When some beet field peon takes a few rares of this stuff,' explained Dr. Fred Fulsher of Mineral County, 'he thinks he has just been elected President of Mexico so he starts out to execute all his Political enemies. I understand that over in Butte where the Mexicans often go for the winter they stage imaginary bullfights in the 'Bower of Roses' or put on tournaments for the favor of 'Spanish Rose' after a couple of whiffs of marihuana. The Silver Bow and Yellowstone delegations both deplore these international complications.' Everybody laughed and the bill was recommended for passage.”16

In a recorded testimony on the effectiveness of the amended 1915 Food and Drug Act, a small drug store owner in El Paso stated:

“I say to the purchaser, ‘I have two kinds of Marihuana, the Mexican Marihuana, which is used for smoking purposes, and the American Marihuana, which is used for medicinal purposes. Now which kind do you want?’

Without fail they reply, ‘Give me the American kind.’ I then advise them that they must be very careful not to smoke the American kind as it is liable to ruin their throat and sometimes causes serious sickness. Invariably they finally decide that they will take the Mexican kind.”17

Evidently, the language succeeded. In 1929, the state of Montana amended its general narcotic law to include marihuana. On the federal level, shortly after Director Anslinger’s bigoted testimony on the Hill, Congress outlawed recreational cannabis under the aptly named Marihuana Tax Act.

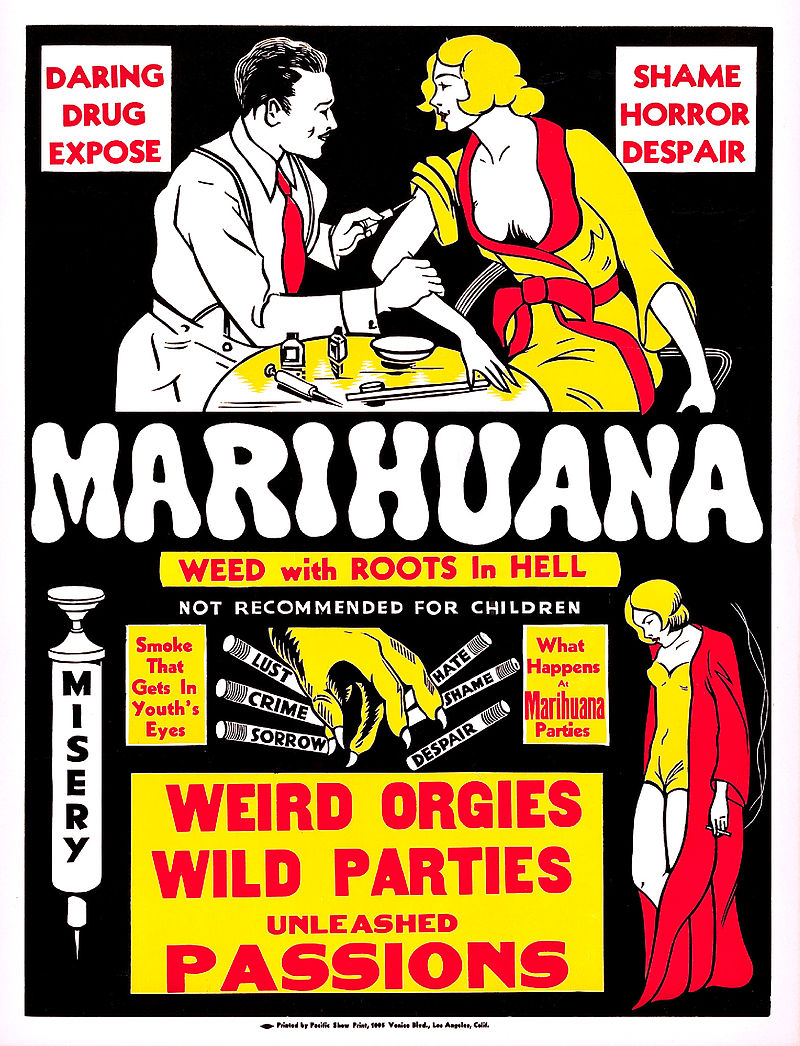

On the cultural front, 1930s Hollywood helped turn public perception against cannabis using similar language. The clearest example of this is the 1936 exploitation film Marihuana, with the theatrical poster calling it the “Weed with roots in HELL.” It was directed by Dwain Esper, who would go on to create the cult film Reefer Madness, deemed to be one of the first movies ever made and a satirical hit in cannabis culture.18

Marijuana and Minorities

While Mexican immigrants took the brunt of the anti-cannabis hysteria, the “evil weed” came to be associated with other repressed minorities in the US.

By the 1930s, supposed cannabis use had been extended to African Americans, particularly musicians. In the city of Nashville, The Tennessean reported that cannabis was used by “society people, musicians, and many negroes.” In Georgia, the Atlanta Constitution alleged that the plant was “gaining many converts among the high school students… and also in the negro sections of the city.”

Cannabis was particularly associated with the then-new genre of jazz music, where blacks excelled. In fact, Director Anslinger kept a file titled “Marijuana and Musicians,” which aimed to orchestrate a national dragnet of jazz musicians. Anslinger did not bother to hide his prejudice during his congressional testimony, stating that “There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the US, and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers. Their Satanic music, jazz, and swing results from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers, and others.”19

The Murder That Killed Marijuana

One of Anslinger’s primary examples of outlawing cannabis was the case of Victor Licata.

In 1933, the then-21-year-old Licata used an axe to kill his parents and three siblings while they slept in the family home in Tampa, Florida. Newspapers of the time reported it to be the work of an "axe-murdering marijuana addict," with sensational headlines like “Stop This Murderous Smoke” and “Reefer Madness Hits Ybor City.”

After learning of the incident, Director Anslinger latched onto the case with a zeal, writing about it in his influential 1937 article “Marijuana, Assassin of Youth." Anslinger alleged that Licata murdered his family due to cannabis-induced hallucinations:

“(Licata) killed his parents, two brothers and a sister while under the influence of a Marihuana 'dream' which he later described to law enforcement officials. He told rambling stories of being attacked in his bedroom by 'his uncle, a strange old woman and two men and two women,' whom he said hacked off his arms and otherwise mutilated him; later in the dream, he saw 'real blood' dripping from an axe.”

Ansliger would later rehash the case during his Congressional testimony that saw the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937:

“It was an unprovoked crime some years ago which brought the first realization that the age-old drug had gained a foothold in America. An entire family was murdered by a youthful addict in Florida. When officers arrived at the home they found the youth staggering about in a human, slaughterhouse. With an ax he had killed his father, his mother, two brothers, and a sister. He seemed to be in a daze...

He had no recollection of having committed the multiple crime (sic). The officers knew him ordinarily as a sane, rather quiet young man; now he was pitifully crazed. They sought the reason. The boy said he had been in the habit of smoking something which youthful friends called 'muggles,' a childish name for marijuana.”

The problem was that there was no evidence that Licata had used cannabis at all. In fact, the suspect had a recorded history of mental illness, and the connection to cannabis came from a detective’s interview with the Tampa Bay Times. The day after the story was published, the detective backtracked on cannabis being the main cause but still held firm on his anti-cannabis stand:

“Maybe the weed only had a small indirect part in the alleged insanity of the youth, but I am declaring now and for all time that the increasing use of this narcotic must stop and will be stopped.”

Less than two weeks later, psychiatrists diagnosed Licata with "dementia praecox with homicidal tendencies." According to their analysis, this made him "overtly psychotic" and "subject to hallucinations accompanied by homicidal impulses." Modern experts suggest it was schizophrenia. Licata was ordered to be committed to the Florida Hospital for the Insane in Chattahoochee, Florida. His medical file does not reference any cannabis usage.

But did cannabis really cause a “crime wave” during the era, as Anslinger and sensationalist headlines of the time would have us believe?

Cannabis and Crime

To understand the perception of cannabis among the general American public, we need to look at the sensationalization efforts by Anslinger and other anti-drug proponents of the time.

Journalists had been tasked with highlighting the dangers of drug use and addiction. However, they needed a new, unfamiliar drug beyond opiates and cocaine as the target, and cannabis fit the bill because much of the general public was not familiar with the plant.19 Therefore, painting a vivid picture of cannabis as the culprit behind crime at the time was a relatively easy feat.

If only following the media coverage at the time, it would’ve been easy to believe cannabis did indeed cause a certifiable crime wave with its more widespread use due to immigration from Mexico and growing general popularity in places like hashish parlors in urban areas. However, delving into the crime data prior to cannabis prohibition and after tells a much different and highly enlightening story.

Crime of all types has been on a general decline in the US — with many upticks and sharp declines over the years since colonial times. Therefore, pinpointing a crime wave associated with only heightened cannabis use in the early 1900s is difficult to do. Let’s take a look at homicide rates to get a snapshot understanding of crime rates between 1900 and 1950.

During these 50 years, homicide rates actually fell from just below 8 per 100,000 to around 5 per 100,000 people. The highest peak in homicide rates during the period actually occurred in the 1920s and 1930s, which happens to coincide with the time of the onset of alcohol prohibition (between 1920 and 1933). Homicide rates went on a steady decline when the alcohol prohibition era ended, which was just before the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937.20

Throughout history, substance prohibition has been a significant topic of debate, with some groups like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) taking the stance that drug prohibition is actually a public health downfall and has been since the early 1900s. This stance stems from the fact that banning drugs, including cannabis, removes any element of quality control or enacting standards while creating a black market that is often rife with violent criminal activity.21

An element of racism was also prominent in the efforts of the anti-drug campaigners in the 1920s and 1930s. The most atrocious crimes were most often attributed to Mexicans and cannabis use, but other races were not unaffected by the stigma. In the early 1930s, during the Great Depression, fear of immigrants and public concern instigated a number of research efforts that linked cannabis to crime, violence, and “socially deviant” behaviors. Many of these were said to be committed by people from underclass communities where the people had been deemed as “racially inferior” because they were not white.22

In contrast, the US Census Bureau of committed people at the time shows that crime rates were not much different among both native-born citizens and immigrants. The commitment rate is the number of people who have been committed to incarceration and does not necessarily reflect the number of people currently incarcerated. With population estimates and adjustments for variances in age among different groups, 140 out of 100,000 native-born individuals were committed in 1930, while only 52 out of 100,000 were foreign-born. This shows that, cumulatively, regardless of the crime, foreign-born individuals were less likely to be incarcerated than people born in the US.23

The LaGuardia Committee

The 1937 Marijuana Tax Act was not without its detractors. One of its strongest opponents was Fiorello LaGuardia, the formidable mayor of New York City. A liberal Republican, LaGuardia was a national political figure and was often cross-endorsed by both parties across the aisle. He was also interested in the effects of cannabis after hearing the findings of the US Army Board of Inquiry that emphasized the harmlessness of the drug.

In 1939, the mayor tasked the New York Academy of Medicine to investigate the effects of cannabis on American society. He wanted an expert and impartial body to “make a survey of existing knowledge on this subject and carry out any observations required to determine the pertinent facts regarding this form of drug addiction and the necessity for its control."

Known as the LaGuardia Committee, the commission released its report in 1944 and was the first in-depth study on the effects of cannabis smoking in the US. The exhaustive 5-year study found that:

- The practice of smoking marihuana does not lead to addiction in the medical sense of the word.

- The use of marihuana does not lead to morphine, heroin, or cocaine addiction, and no effort is made to create a market for these narcotics by stimulating the practice of marihuana smoking.

- Marihuana is not the determining factor in the commission of major crimes.

- Marihuana smoking is not widespread among school children.

As Mayor LaGuardia noted, “The report of the present investigations covers every phase of the problem and is of practical value not only to our own city but to communities throughout the country. It is a basic contribution to medicine and pharmacology. I am glad that the sociological, psychological, and medical ills commonly attributed to marihuana have been found to be exaggerated insofar as the City of New York is concerned.”

Upon its release, the report angered the irascible Anslinger by debunking many of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics’ claims. He denounced the five-year study as “unscientific” and demanded that any future research on the effects of cannabis be made only with his own personal approval.

In response, he commissioned his own “scientific” study through the American Medical Association in 1944. Anslinger’s study fell back on racism, where the experimental group was composed of 34 black men and only one white participant. Supposedly, “Those who smoked marijuana became disrespectful of white soldiers and officers during military segregation."

Roughly 30 years later, a presidential commission under the Carter administration would find that Anslinger’s study had no scientific basis and would share much of its conclusions with the LaGuardia report.

References

1. N.T. Dunford, “Specialty Oils and Fats in Food and Nutrition”, 2015. https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9781782423768/specialty-oils-and-fats-in-food-and-nutrition

2. Cherney, J., and E. Small. 2016. “Industrial Hemp in North America: Production, Politics and Potential.” Agronomy 6(4): 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy6040058

3. 1850 Census: Compendium of the Seventh Census. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1850/1850c/1850c-06.pdf

4. Steinhauer, Jason. “The History of Mexican Immigration to the U.S. in the Early 20th Century.” ISSN 2692-2185. https://blogs.loc.gov/kluge/2015/03/the-history-of-mexican-immigration-to-the-u-s-in-the-early-20th-century/

5. Malmo-Levine, D. (2021, April 2). Dr. H. H. Kane and the 19th century “hash-heesh” smoking parlors of NYC ... Cannabis Culture. https://www.cannabisculture.com/content/2021/04/02/dr-h-h-kane-and-the-19th-century-hash-heesh-smoking-parlors-of-nyc/

6. Gutiérrez, Ramon. “Mexican Immigration to the United States.” Published online 29 July, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.146

7. Long, Trish. “1915: El Paso becomes first city in United States to outlaw marijuana”. El Paso Times, Nov. 14, 2019. https://www.elpasotimes.com/story/news/2019/11/14/el-paso-history-pot-possession-first-city-outlaw-weed-tbt/2579079001/

8. Gieringer, Dale. “The Origins of Cannabis Prohibition in California.” June 1999 Contemporary Drug Problems 26(2) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242120559_The_Origins_of_Cannabis_Prohibition_in_California

9. Dudley, Elyssa. “The nation's first marijuana raid likely happened in Los Angeles.” KPCC September 19, 2014. https://archive.kpcc.org/programs/offramp/2014/09/19/39399/the-nation-s-first-marijuana-raid-likely-happened/

10. Beatriz Caiuby Labate; Clancy Cavnar (March 25, 2014). Prohibition, Religious Freedom, and Human Rights: Regulating Traditional Drug Use. Springer Science & Business Media. https://books.google.com.ph/books?id=DLWNBAAAQBAJ&pg=PT236&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

11. Marijuana: A Study of State Policies and Penalties (PDF), National Governors' Conference Center for Policy Research and Analysis, November 1977. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/43880NCJRS.pdf

12. Gilmore, Brian, "Again and Again We Suffer: the Poor and the Endurance of the 'War on Drugs,'" University of the District of Columbia Law Review (Washington, DC: The University of the District of Columbia David A. Clarke School of Law, 2011) Volume 15, Number 1, p. 64.

13. Borchardt, Debra. “Pfizer, Eli Lilly Were The Original Medical Marijuana Sellers.” Forbes Magazine, Apr. 8, 2015. https://www.forbes.com/sites/debraborchardt/2015/04/08/pfizer-eli-lilly-were-the-original-medical-marijuana-sellers/?sh=65547f793026

14. Campos, Isaac. “Is the Word Marijuana Racist?” https://www.thedrugpage.org/racism-marijuana-nomenclature

15. Halperin, A. (2018, January 29). Marijuana: Is it time to stop using a word with racist roots? The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jan/29/marijuana-name-cannabis-racism.

16. Montana Standard, Jan 27. 1929: 3

17. Campos, Isaac. “Mexicans and the origins of marijuana prohibition in the United States: a reassessment.” Social History of Alcohol and Drugs, Volume 32 (2018) https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/SHAD3201006

18. Stemme, Joe (September 4, 2005). "What's the Worst Movie Ever?". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2005-sep-04-tm-letters36.1-story.html

19. Solomon, Robert. “Racism and Its Effect on Cannabis Research.” Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. March 2020; 5(1): 2–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7173675/#B14

19. Siff, S. (2014, May). The illegalization of marijuana: A brief history. Origins. https://origins.osu.edu/article/illegalization-marijuana-brief-history?language_content_entity=en

20. Fischer, C. (2010, June 16). A crime puzzle: Violent crime declines in America. Berkeley. https://news.berkeley.edu/2010/06/16/a-crime-puzzle-violent-crime-declines-in-america/

21. Against drug prohibition (1995) American Civil Liberties Union. Available at: https://www.aclu.org/documents/against-drug-prohibition (Accessed: 02 October 2023).

22. Public Broadcasting Service. (n.d.). Marijuana timeline | busted - america’s war on marijuana | frontline. PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/dope/etc/cron.html

23. Moehling, C., & Morrison Piehl, A. (2007, November). Immigration and crime in early 20th century America - NBER. NBER.org. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w13576/w13576.pdf

The information in this article and any included images or charts are for educational purposes only. This information is neither a substitute for, nor does it replace, professional legal advice or medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. If you have any concerns or questions about laws, regulations, or your health, you should always consult with an attorney, physician or other licensed professional.